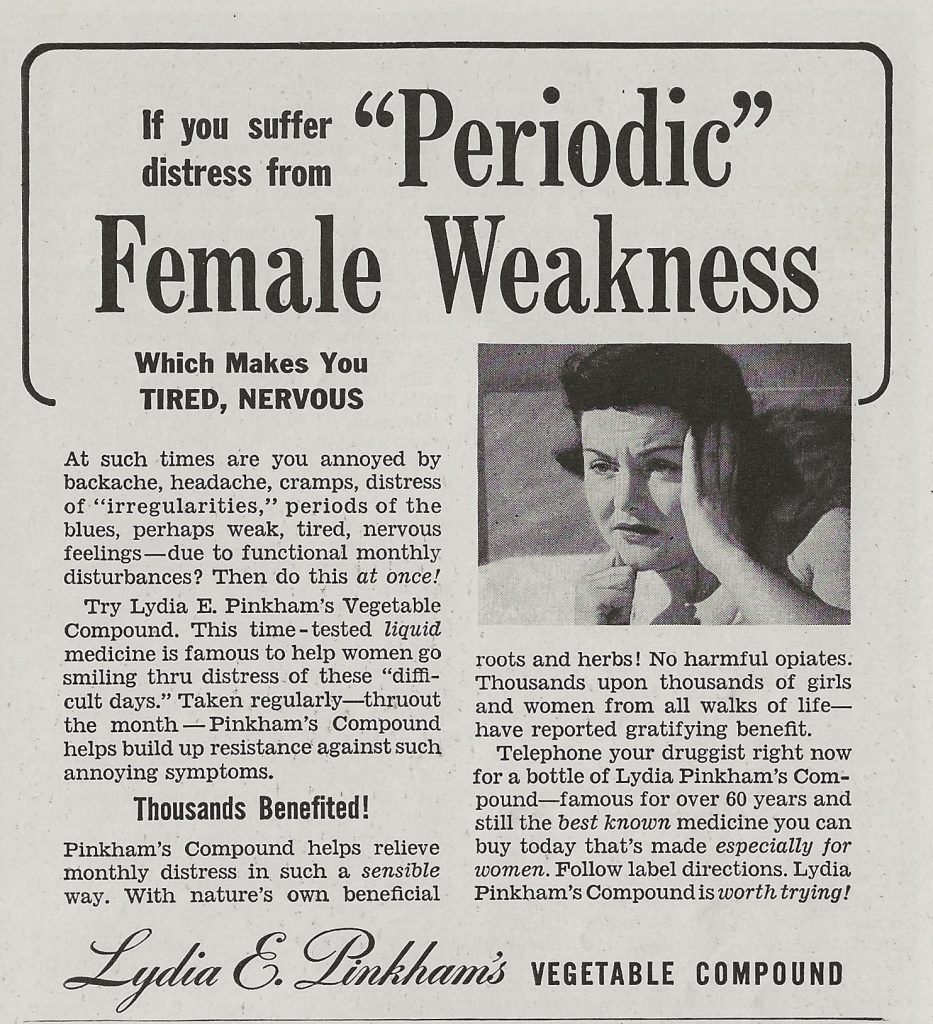

This ad, from a 1942 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, offered women a solution for menstrual pain and irritability. Although, given the propriety of the time, this was merely hinted at with turns of phrase like “periodic female weakness” and “functional monthly disturbances.” The cure was the widely popular Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. When taken regularly, it promised resistance to symptoms suffered during the “difficult days.”

Who Was Lydia Pinkham?

Mrs. Lydia Estes Pinkham first concocted the compound in 1873 in her home kitchen in Lynn, Massachusetts. Her formula was a mixture of alcohol preservative with roots and herbs, including black cohosh, life root, unicorn root, pleurisy root, and fenugreek seed. These botanicals were alleged to cure conditions of the uterus, prevent miscarriage, and reduce the inflammation associated with menstrual cramping and menopause.

The 54 year old Mrs. Pinkham had taken up the hobby of producing home remedies from her family’s recipe book. In the nineteenth century, medications prescribed by doctors were often expensive and considered dangerous. Thus, it was still a common practice for housewives to develop herbal remedies at home.

Mrs. Pinkham shared her compound freely with her neighbors and soon word began to spread of its effectiveness. Of course, part of the remedy’s success may have been from its 20 percent alcohol content. At least, this might have made the sufferer more congenial to their monthly situation!

An Enterprise is Born

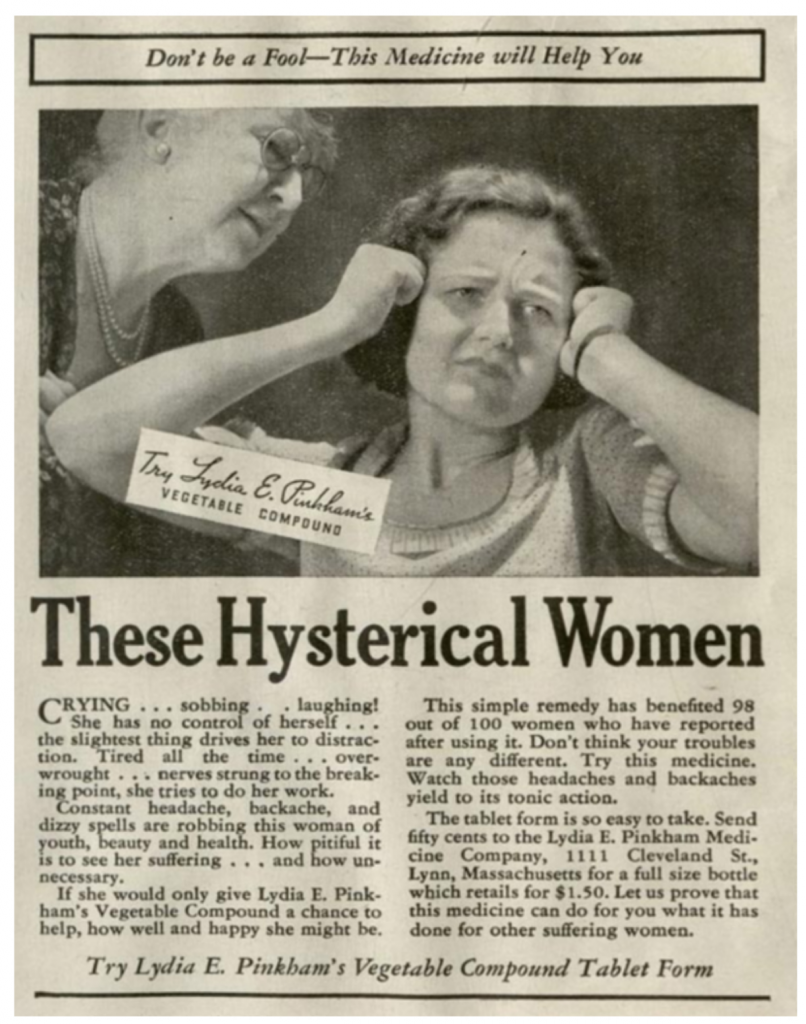

As the story goes, facing a recent economic downturn, Mrs. Pinkham reluctantly considered the possibility of profiting from her compound. With the help of her three sons, Mrs. Pinkham packaged her product for sale and transformed her basement into a factory. The family took out a mortgage on their home and used $1000 of the proceeds to fund an advertising campaign out of a New York agency. Lydia’s image appeared on the bottle and ads, with her grandmotherly visage meant to inspire trust.

During the 1800s, the market was certainly rich with snake oil salesmen claiming to cure every disease known to man. But Mrs. Pinkham’s compound stood apart. For one, it had not been born out of a mere money-grabbing scheme, and two, it actually did seem to work. And once it’s effectiveness against menstrual pain was established, the formula was soon positioned to treat other female ails and even increase virility. At one point, the tagline read: “There’s a baby in every bottle.”

The Department of Advice

With widespread marketing, Mrs. Pinkham quickly gained notoriety as a figurehead for women’s health. She even developed a “Department of Advice”, encouraging women who were dissatisfied with their physicians’ care to write to her with questions. This was a welcome relief for many women, when at the time, male doctors were particularly insensitive to female issues. As an example, the accepted solution for menstrual pain was to remove to ovaries – a procedure that carried a 40% mortality rate.

Even after her death in 1883, ads continued to encourage readers to write to Mrs. Pinkham. In 1902, Ladies Home Journal attempted to prove the company’s deception by running an exposé photograph of the late Mrs. Pinkham’s tombstone. The company responded by saying they had never misled anyone. The “Mrs. Pinkham” now taking letters was in fact Lydia’s daughter in law, Jennie. This “Dear Abby” precursor continued to grow a following and helped to ensure the brand’s staying power.

Lily the Pink

In 1906, the Pure Food and Drug Act required patent medicines to disclose ingredients on their labels. Pinkham’s company was also barred from advertising some of their wilder medical claims (such as the treatment of prolapsed uterus). For the first time, buyers were also made aware that the compound contained a hefty alcohol content. However, this did nothing to dampen enthusiasm for the product.

The compound even found an unexpected new market among men during the Prohibition Era, where it was enjoyed in the form of a 40 proof tonic. Lydia was memorialized in a popular drinking song known as “The Ballad of Lydia Pinkham” or “Lily the Pink”. The song poked fun at the kind of “complaints” such intoxicating medicines were really meant to cure.

While various versions of the song had circulated in folklore, the UK comedy group ‘The Scaffold’ recorded their interpretation in 1968. “Lily the Pink” held the top spot on the UK Singles chart for four weeks running. (As you watch the performance, you might recognize the chap on the left as Peter Michael McCartney, brother of the famous Beatle.)

147 Years and Counting

Sales of the beloved product continued throughout the 20th century, also gaining ground overseas just before World War 1. By 1925, the company was grossing the equivalent of $55 million annually by today’s measure. All this, despite various attempts by medical experts and the National Institute of Health to disprove the formula as quackery. Early advertisements were also criticized for demonizing the concept of “women’s weakness” and emotional hysteria.

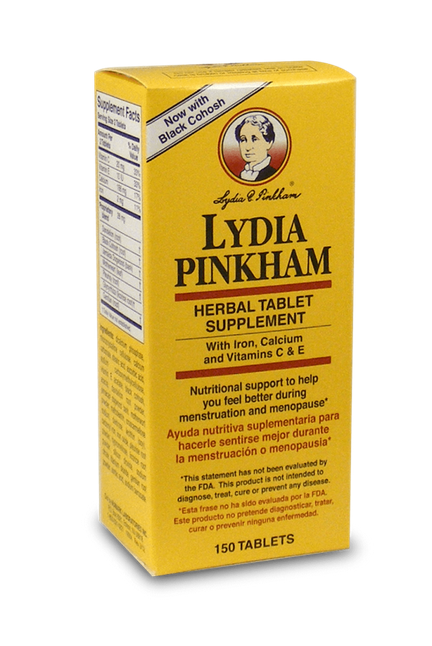

The brand remained under control of Pinkham’s family until the 1930s. Since that time, various other laboratories have adopted the brand and sold their imitation of Pinkham’s original recipe, minus the alcohol. Sales have continued throughout the 20th century and beyond. As recently as 2004, Numark Laboratories in New Jersey began marketing their version of “Lydia Pinkham’s Herbal Remedy”, largely based on her original recipe, with some additional herbs and vitamins. You can still find Mrs. Pinkham in your pharmacy today.

Sources and Additional Information

Horwitz, Rainey, “Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound (1873-1906)”. Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-05-20). ISSN: 1940-5030

“A Product of its Time: Lydia Pinkham” by Chris Root, Denver Library – Part 1 and Part 2. Examines the legacy of the patent medicine’s advertising claims.

“Lydia’s Medicine – 130 Years Later” by Cecil Munsey, 2003. Features many more photographs and information on the Pinkham business.